OVERHEAD RATIOS – PART II - DRIVEN TO A PREMATURE GRAVE BECAUSE OF INCESSANT, UNCEASING AND RELENTLESS ATTENTION TO NONPROFIT OVERHEAD RATIOS

OVERHEAD RATIOS – PART II - DRIVEN TO A PREMATURE GRAVE BECAUSE OF INCESSANT, UNCEASING AND RELENTLESS ATTENTION TO NONPROFIT OVERHEAD RATIOS

Andrea McManus, ViTreo Group Inc

December 3rd 2019

“Proper Care and Feeding

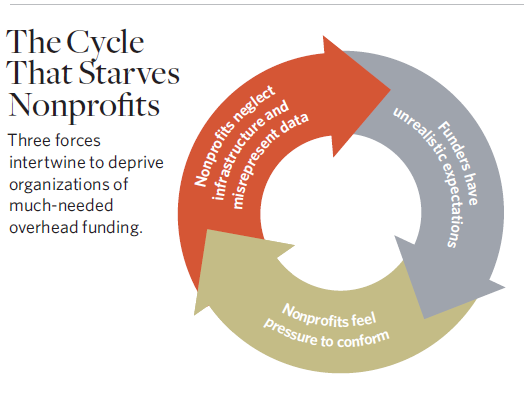

Although the vicious cycle of nonprofit starvation has many entry points and drivers, we believe that the best place to end it is where it starts: Funders’ unrealistic expectations.”

Last week’s The Provocateur tackled one of the biggest obstacles nonprofits and fundraisers face. The endless and unceasing overhead ratio conversation.

I completely agree foundations and donors should know how their funds and donations are being spent. That’s a given — any of us making a donation or a purchase or other financial decision want the answer to this question: Can I trust you? If we can’t, we put our wallets or credit cards away and take our money elsewhere.

In the charitable world, however, these facts don’t tell the whole story. When it — overhead ratio — becomes the only driver for choosing one beneficiary over another, the decision is being made without all the essential facts. In other words, the big picture. All too often nonprofits feel they have no other avenue than to be the proverbial contortionist at the circus with their program numbers…trying to make them fit into the “low overhead” scenario (“scenario” - a postulated sequence or development of events - a lovely definition that somehow fits perfectly!).

This leads to nonprofit starvation.

So, what do we do about this? At the core of the conversation, what’s driving the problem is the perceptions of those funders and donors, and often our own boards. They believe nonprofits and fundraisers need to keep overhead investment within an often arbitrarily decided upon limit by government and foundations. And it’s always low. We need to change these expectations and create a new conversation to one that focuses more on the end result, and less on the cost of getting there.

From Scott Decksheimer, ViTreo co-founder, in his recent blog post, Does Fundraising Need a Public Makeover?:

‘Three years ago, I was attending the International Fundraising Conference in San Francisco, and had just finished signing the legal papers to form the Association of Fundraising Professionals (AFP) Canada and officially become the Chair. While there, I was talking with Neil Gallaiford from Toronto and we discovered a common challenge – a complete lack of knowledge or understanding of fundraising by media, self-proclaimed watchdogs, government representatives, and even our own CEOs and Boards of Directors!’

A few years ago, we were creating a development plan for a client and I was presenting the long term strategic goals to the board. The first question the board chair, a (very) senior financial person in the community had was this: “How much is this going to cost?”, followed by the statement “We can’t spend any money on this.” I don’t suppose those would have been the top questions on his mind when he was weighing the pros and cons of an investment deal!

I was also the guest on a noon hour radio show during the holiday season not that long ago, and taking questions about giving to charities. A gentlemen who called said, “You are the problem. Charities shouldn’t be paying people like you and they shouldn’t have any staff at all, all volunteer or no go.”

Tell that to a university!

Funder/Donor Unrealistic Expectations

In The Nonprofit Starvation Cycle, authors Ann Goggins Gregory and Don Howard do an excellent job of addressing this:

“The nonprofit starvation cycle is the result of deeply ingrained behaviors, with a chicken-and-egg-like quality that makes it hard to determine where the dysfunction really begins. Our sense, however, is that the most useful place to start analyzing this cycle is with funders’ unrealistic expectations. The power dynamics between funders and their grantees make it difficult, if not impossible, for nonprofits to stand up and address the cycle head-on; the downside to doing so could be catastrophic for the organization, especially if other organizations do not follow suit. Particularly in these tough economic times, an organization that decides—on its own—to buck the trend and report its true overhead costs could risk losing major funding. The organization’s reputation could also suffer. Resetting funder expectations would help pave the way for honest discussions with grantees.”

Exactly. Many of us (including funders) are aware that, in order to survive, charitable organizations must resort to reporting low overhead numbers. In the work ViTreo does with its clients, in this blog and with colleagues, I often talk about the importance of nonprofits taking a lesson from for-profits and adopting a business model for their organizations.

There is much we can attribute to the low overhead expectation and its effect on nonprofit impact.

If we look at for-profits, investment in hiring, rewarding and retaining the best people is typically a high priority, and often the basis for their success. Why? It’s better for the bottom line and increases shareholder value. Without them, the business will eventually fail. If we contrast that to our world, there is often little investment in creating an attractive package for employees — low wages, too many hours and few benefits lead to frustration and burnout, and finally high rates of staff turnover. And the resulting drag on impact. You don’t need an MBA to understand this.

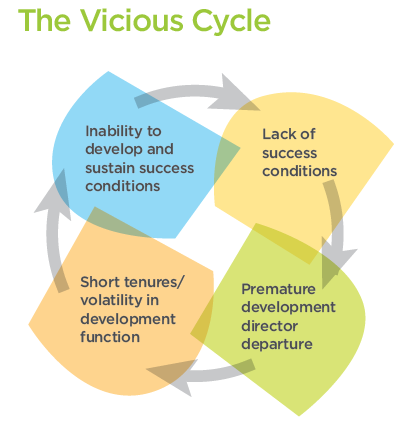

In CompassPoint’s 2013 report UnderDeveloped: A National Study of Challenges Facing Nonprofit Fundraising revealed:

“At many nonprofits the development director position has been vacant for months, or even years…

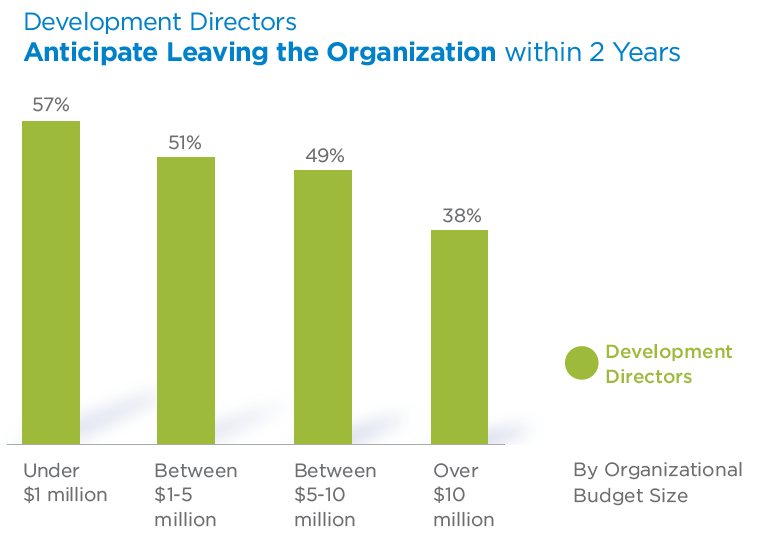

Our data suggest a high level of instability and uncertainty in the development director position in nonprofit organizations. Among the concerns: high turnover, long vacancies, performance problems, and the fact that large numbers of development directors are not committed to careers in fundraising. Most concerning is the combination of long-time vacant positions—especially among smaller organizations — and high rates of anticipated departure among current development directors…

The development director is commonly labeled a ‘revolving door’ position, and ‘the hardest to fill and retain’ by executives, board members, funders, and capacity builders alike.”

Given the non-competitive salaries plus the difficult and often unrewarding work, why would anyone want to jump in to this role? Most of us want to do good in the world, but when that becomes too hard, why wouldn’t we jump ship and take our skills and talents elsewhere?

And why should other sectors be able to pay market competitive compensation for social workers employed by them than many social workers (as well educated, by the way) employed in the charitable sector? In fact, many nonprofits in the human resources sector, provide services to government, with those same social workers! Why would they view investment in retaining social workers (who do vitally important work) over a similar investment in the employees of charitable organizations — who also do vitally important work and if the nonprofit is well run, are more strategic and far-reaching in their ability to accomplish this mission. At the least, it’s unfortunate, it’s a sad state of affairs and it’s infuriating.

And it’s not just in the human services sector. The nonprofit sector is home for hundreds of thousands of skilled, highly educated and accomplished individuals. No more or less than in the private sector. Yes, they are dedicated to their cause and, in many cases, working their passion. But passion can be diminished when salaries and resources are decimated and their work is consistently and publicly undervalued.

“Overall, 40% of development directors reported that “fund development is my current field of work, but I am not sure if I will stay in it for my entire career.” Even without knowing the degree of professional competency among survey respondents, this nonetheless reflects a significant potential drain of fundraising experience from the sector in the coming years.”

I’m not the first to say this, but you get what you pay for. If a nonprofit organization doesn’t have the budget to pay an appropriate salary and include training and professional development to a skilled individual (a scenario often seen at smaller nonprofits), it may well be forced into the position of hiring someone with lesser skills or overloading them.

Many people are not aware universities are nonprofit organizations. Yet…again…market competitive salaries, benefits and pensions, professors and other staff are in place. Because of government funding, private donations and high profile fundraising. How can smaller charities compete?

Another critical need for nonprofit investment is technology infrastructure. In the business world, current technology is a given (mostly). It’s difficult to run a business without it. Yet…we are expected to “make do” and often “make without.” If it wasn’t so frustrating and the stakes weren’t so high, this worldview of our sector would be laughable. Instead, it brings many nonprofits to their knees…literally.

Stopping the Nonprofit Starvation Cycle

As I mentioned in last week’s blog post, and again, according to the research done by Goggins Gregory and Howard, we need to begin at the beginning (of course). At the root of the problem. And that is to find a solution to change the narrative, foundations and government (and donors) must also change. To stop the starvation — the withholding of funds and grants which creates a poverty mentality within nonprofits and directly impacts the good we strive for, we must work with these stakeholders to influence and alter their belief system.

Having said that, I am well aware it’s one of those easier said than done statements!

It’s going to take a concerted effort to shift how government and foundational perception of how the charitable sector allocates funds. Where do we start?

As nonprofits and fundraisers, we need to do a better job of building and telling that story. The stories we tell about the good we do, and the people, situations, institutions who benefit from our work, must be more compelling in order to shift expectations. The key question they will want answered is always going to be “Why?” “Why should <insert foundation/donor name here> give you any money?” If we are not answering that question in a way that compels them to grant or donate, our cause is lost. After all, it’s not as if there aren’t other worthy causes, which may be telling a better story. And that story must do a stellar job of why we need this amount of funding or donations to achieve our mission.

A well-crafted story, along with the facts for proof-points, is what’s needed.

And here’s another thought. Why do we talk about overhead and fundraising expenses relative to fundraising costs? Why isn’t the conversation about “investment” in impact, people and community? Where else can you invest $100 or $1000 and see a 100% or even 200 or 300% + ROI because your donation to “overhead” enabled that organization to raise another $XXX. Just think about that for a bit.

Our audience is not going to alter their perception on its own. We must help them. We need to understand what is important to them, what drives their actions or motivations, and we need to tell stories that align with their worldview. A foundation isn’t a person, but the decision-makers within the foundation are. Although they have a specific mandate, their decisions are going to be based on emotion. It’s how our brains work which drives our choices (watch for future blog on this).

To achieve this means reviewing how we currently tell our stories. Are they told from what WE think is important? Because that’s not effective. Whether it’s campaign, or a case for support or grant application or other fundraising effort, understanding our audience is the key.

In Seeing through a Donor’s Eyes, the back cover says:

“[Tom Ahern], among America’s most experienced case specialists, shares his secrets for selling your vision and mission effectively. In their acclaimed business book, Made to Stick, The Heath Brothers prove it’s the curse of knowledge that ruins most insiders (i.e. fundraisers) attempts to persuade the outside world (i.e., prospective donors).”

What I’m saying here is that it is up to us — the charitable sector. We need to take responsibility for changing the conversation. We didn’t start it, but there is no point in dwelling on that fact. If we want things to be different, we will have to be different. If nothing changes, nothing changes. It won’t be easy, but it is crucial for our future and the future of those whose lives we strive to change.

As Scott, ViTreo co-founder, wrote in his recent blog post, “We as leaders need to address the narrative internally – in order to help change the conversations externally. If our Boards don’t know the facts, how can we expect the media to respond, or watchdogs to change their ways.”

We also need to extend that narrative externally to a broader audience — to include funders, donors, governments and other stakeholders.

More to come on this next week as the conversation continues about what the charitable sector can do to end one conversation about overhead and start another, newer, more accurate and successful narrative. Hint: We (charitable sector) play a big part in the solution again….Have a great week!

Check out ViTreo's Braintrust as we bring you additional insights into what is and what will be important in philanthropy through our Weekly News Recap and our Podcast.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Andrea McManus, Chair, Board of Directors, Partner

ViTreo Group Inc

Andrea McManus is a Partner with ViTreo with over 30 years’ experience in fund development, marketing, sponsorship and nonprofit management. A highly strategic thinker and change maker, Andrea has worked with organizations that span the nonprofit sector with particular focus on building long-term and sustainable capacity.